|

Listen to this article here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Growing up in Chicago, Illinois, Mae Jemison always had her sights set high. She was a trained ballerina but developed a deep love for science. Witnessing a lack of female representation in NASA’s astronaut program, she found inspiration from Nichelle Nichols, who played Lieutenant Uhura on Star Trek.

At the age of 16, Jemison was accepted into Stanford University. Jemison received two bachelor’s degrees, one in chemical engineering and the other in African American studies. After concluding her undergrad studies she was accepted by Cornell Medical School. While in medical school she traveled the world and participated in several student-led initiatives. Jemison later joined the Peace Corps.

Her journey took a turn in 1983 when Sally Ride became the first American woman in space. Jemison decided to apply for NASA’s astronaut program in 1985 but due to the Challenger explosion disaster of 1986, the agency paused accepting new applicants.

She didn’t let this setback stop her from chasing the stars. Jemison reapplied in 1987 and found herself in the esteemed group of 15 trainees selected out of 2,000 applications.

Two years later, they selected her as a Mission Specialist for the space shuttle Endeavor. When the mission launched in 1992, Jemison made history as the first African-American woman in space.

This was a monumental achievement for Black women in America. But she wasn’t the first African American woman to make history in the realm of science.

Patricia Cowings, NASA Psychologist

Twenty years before Mae Jemison boarded Endeavor, Patricia Cowings was the first Black woman to receive science astronaut training with NASA. Cowings’ education was in Psychology, which may come as a surprise considering her involvement with NASA. Her formal title is Aerospace Psychophysiologist and her work involved creating treatments for motion sickness in space. At the age of 75, she is still actively employed by the space agency and currently researches spatial disorientation that occurs during launch and re-entry.

Carolyn Parker, Atomic Physicist

Miss Carolyn Parker was the first Black American to earn a physics postgraduate degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Between 1943 and 1947 she was employed at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio. There she worked on the Dayton Project, a branch of the Manhattan Project famous for its development of atomic weapons. Her sister said Parker’s work was so secretive that she couldn’t even discuss it with her family.

After leaving the Dayton Project she returned to MIT to obtain a doctoral degree. However, Parker developed leukemia due to her exposure to radioactive material during her work. This prevented her from finishing her doctoral program. She ultimately passed away in 1966.

Mary Elliot Hill, Chemist

Formally educated in analytical and organic chemistry, Mary Elliot Hill stands as one of the earliest known Black chemists. Hill earned her bachelor’s degree from Virginia State University in 1929. She taught at many different universities, including Kentucky State University where she studied ultraviolet spectrophotometry and ketene synthesis.

Her work didn’t end in the laboratory. Hill used her trailblazing achievements to inspire other Black students to engage in chemistry. She started chapters of the American Chemical Society at several historically Black colleges and universities.

Related Stories

Beebe Steven Lynk, Pharmaceutical Chemist

Predating Mary Elliot Hill was Beebe Steven Lynk. Born in 1872, Lynk grew up in Mason, Tennessee. She graduated from Lane College in 1892 and married Dr. Miles Vandahurst Lynk, the founder of the Medical and Surgical Observer, the first medical journal to be edited by a Black man.

Together with her husband, the couple founded the University of West Tennessee. She then gained a degree in pharmaceutical chemistry. Lynk became a professor of medical Latin botany at the university she created with her husband. In 1896, she wrote a book titled Advice to Colored Women, which aimed to uplift the social status of Black women through education.

The Future of Black Women in Science

With a colorful history of many decorated African American women who have paved the way for the next generation, the only way to go is up. Unfortunately, the numbers don’t indicate a very inclusive workforce.

According to a 2019 report from the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, only 14% of women in STEM are Black. Another study from the Pew Research Center shows that Black women in STEM make less than their colleagues.

Despite these disparities, there are growing efforts to ensure Black women have a seat at the table.

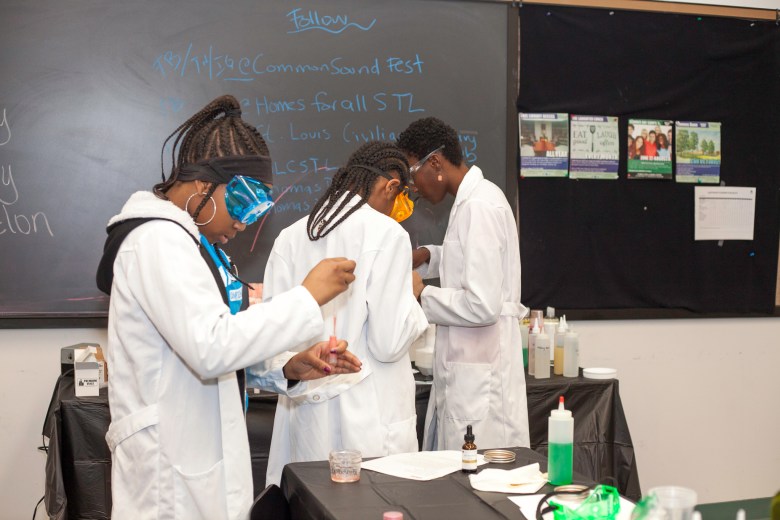

Black Girls Do STEM is an organization that works to get more Black girls and women involved in science. They bring role models like the women highlighted in this article to shared spaces with young Black girls who have a knack for math and science.

The program supports students from grade school to college, preparing them for the STEM workforce. Through boosting confidence and increasing engagement Black Girls Do STEM is working to make sure Black women have a permanent place in the world of science.